Envisioning Regenerative Urban Futures through Foresight Methods

How can cities move beyond reactive planning and start imagining regenerative futures? This blog introduces foresight tools, like the Futures Triangle, Scenario Mapping, and Causal Layered Analysis, as methods to break free from short-termism in urban planning. It highlights how these tools can open up space for inclusive, long-term thinking and support more adaptive, equitable urban environments.

Marie Urfels

6/3/20258 min read

This spring I had the privilege to participate in a collaborative foresight cycle on the futures of our digital urban layers at Media Evolution. This workshop got me thinking about the potential of bridging foresight methods with urban planning methods to explore where we want our urban futures to be heading and what structural barriers we need to break to create regenerative urban futures.

In this article, we explore what foresight methods can offer for urban planning and the ongoing development of our cities, how they can help us build more sustainable and regenerative environments that respond to the needs of our communities and the natural world.

Rethinking Urban Planning: Lessons from the Past

Urban planners are traditionally trained in administrative tasks, strategic thinking, resource allocation, and policy development. These skills are essential to managing a city. However, throughout the past centuries, many urban planning strategies have focused primarily on linear short- to medium-term impacts, typically covering a 10- to 15-year horizon. As a result, pluralistic long-term developments are often not considered.

Take, for example, the widespread push for motorization, the vision of cities becoming highly accessible by car. While this strategy succeeded in increasing mobility, it also led to destructive outcomes, including air pollution, urban sprawl, and the degradation of public space. This is just one example of how well-intentioned linear plans can result in unintended plural futures.

Today, with growing awareness of the complex, interconnected nature of urban systems, and the influence of global and local uncertainties, there is an urgent need to expand the skillset of urban planners and researchers. As highlighted by the Stanford Social Innovation Review, planning for the future now requires us to move beyond conventional approaches and engage with the long-term impacts of our decisions.

Of course, we cannot predict the future. But foresight methods can help us - as planners, researchers, or community members - envision multiple alternative futures. Rather than following a single, status quo-driven path, foresight allows us to explore and prepare for diverse uncertainties the future holds. It empowers us to adapt our cities to future challenges and align them with emerging values and systems, thereby making them more resilient and responsive to change.

The Power of Collaborative Foresight in Urban Futures

To turn these future visions into strategic actions, the process must be collaborative. Creating inclusive, regenerative urban futures requires the involvement of diverse participants from a wide range of communities, individuals with different professional backgrounds, lived experiences, and identities. When these voices come together, they can co-create futures that are not only possible and plausible, but also preferable and desirable.

Importantly, these voices must extend beyond planners and policymakers. They must include those who are often left out of traditional planning processes: residents with limited access to decision-making, youth, marginalized groups, and others who represent the full diversity of urban life.

Urban planning is inherently complex, dynamic, and deeply contextual. This complexity calls for foresight approaches that are tailored, inclusive, and grounded in both qualitative and systemic analysis. While foresight can include quantitative tools, its greatest strength in the urban context lies in being exploratory, causal, and adaptive, qualities that mirror the evolving nature of cities themselves..

But once diverse perspectives are brought together, the next step is to ask: What kinds of futures can we imagine and which ones do we want to pursue? This brings us to a key idea in foresight: the plurality of futures.

Imagining Plural Futures

To build robust scenarios of the future, we first need to recognize something essential: futures are plural. They are imagined, constructed, and created. They are not just extensions of the past. They are shapable.

We, as urban residents, hold the power to shape our futures. Through strategies, planning, and visioning, we can decide how we want our environments to evolve over time. And again, there is no one “right” future. There are many narratives, many directions. Foresight isn’t about prediction, but about possibility. To engage with these possibilities in practical ways, we must learn to spot the subtle signals that hint at change already underway.

Reading the Signals of Change

A core concept in foresight is the signal - a small, emergent change we can observe in our cities that may indicate larger transformations ahead. These signals are pockets of disruption or innovation that hint at how the urban future could unfold. By paying attention to them, we can begin to sense what kinds of futures are starting to take shape. Just as importantly, we can identify the structural facilitators that help these changes grow and the barriers that might slow or prevent their adoption.

So, what do some signals of change look like in our urban environments today?

Rewilding urban areas: The rise of biodiversity-rich zones, such as pollinator corridors, or urban forests, reflects a shift toward more ecologically regenerative cities.

Urban agriculture initiatives: Rooftop farms, community gardens, and urban farms in the green belt surrounding a city, vertical agriculture systems can provide seasonal, local food options for urban dwellers while strengthening food resilience.

Circular economy practices: Initiatives focused on sharing, repairing, reusing, and upcycling, such as tool libraries, clothing swaps, or repair cafés, are becoming more visible in urban neighborhoods.

Community hubs and solidarity spaces: Emerging spaces designed to foster connection among diverse residents, especially those often marginalized by formal planning systems, signal a push toward more inclusive urban cultures.

Tactical or pop-up urbanism: low-cost experiments - like temporary parks, seating spaces, street art, or pedestrianized zones - test alternative uses of public space and challenge conventional ideas of how cities can function.

These signals may seem small, but they represent the seeds of broader transformation. When recognized early, they can guide planners, policymakers, and communities in shaping futures that are more inclusive, regenerative, and imaginative.

For instance, here in Malmö, we can already see how tactical urbanism is influencing the city’s approach to public space. Seasonal strategies have transformed streets and parking lots into pedestrian-friendly, community spaces during the warmer months, typically from April to October. These temporary shifts are not just experiments, they’re part of a larger reimagining of urban mobility and placemaking.

We’re also witnessing the emergence of community-driven initiatives that support circular economy values and social regeneration. Projects like Ödet and Drevet are building stronger networks around reuse, repair, and community-focused urban development. Meanwhile, spaces like The House and the Nordic Mom Lab provide platforms for women and mother entrepreneurs to grow their ventures, connect with others, and feel seen and supported in both their professional and personal identities.

These local signals are not isolated trends - they are part of a larger landscape of shifting urban dynamics. But to truly grasp their potential, we must also learn to navigate the uncertainty that surrounds them. Change is rarely linear, and the future is not a fixed destination. It unfolds in complex, sometimes unpredictable ways. That’s why foresight must go hand in hand with flexibility and openness.

Facing Uncertainty: Beyond Predictive Planning

Equally important in foresight is our relationship with uncertainty, especially weak or unexpected uncertainties that might seem unlikely, distant, or difficult to trace, yet could have major impacts on reshaping our urban lives. These could include sudden technological disruptions, shifts in cultural values, changes in life due to climate change, or unexpected political transformations that redefine urban governance.

Traditional urban planning has often relied on predictive models that assume linear progressions based on past trends. Foresight, by contrast, invites us to ask: What could happen? What is emerging? What signals suggest change? It encourages us to stay open to the unexpected and to prepare for a range of possible futures, not just the most probable one.

This requires a mindset shift. We must leave space in planning processes to include interdisciplinary actors, diverse community stakeholders, draw connections between signals, and hold open conversations about uncertainties.

Mapping Future Scenarios Across Key Dimensions

When we explore scenarios of the future, we look at different dimensions. These often fall into at least five or six key categories: social, economic, environmental, political, value-based, and sometimes technological or safety-related factors.

Within each of these categories, we can use the futures triangle to identify:

Signals of change

Drivers that enable certain developments

Structural elements that shape long-term pathways.

A major focus is on identifying weak signals and uncertainties — especially those “unknown unknowns” that might be hard to anticipate but critical to consider. We ask: What do we know and what do we not know? What might happen? What could change dramatically? These insights can help us develop alternative scenarios of the future and thereby explore the impact of diverse future events.

Scanning the Horizon

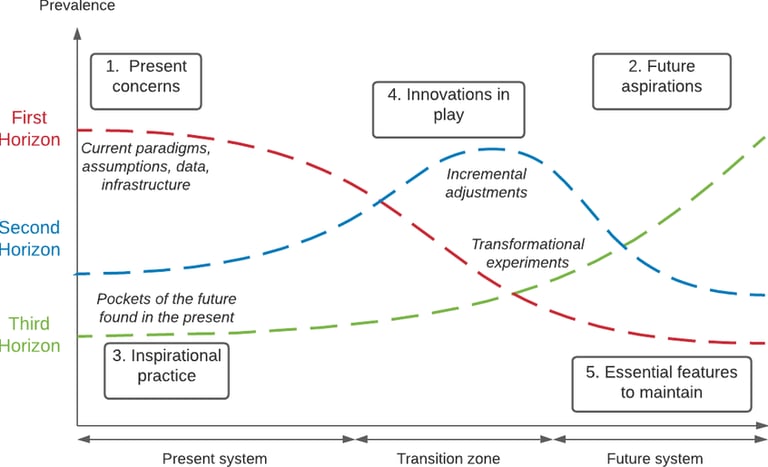

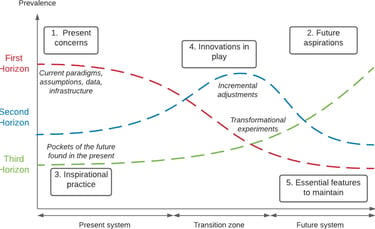

So what is on the horizon for us? What trends, events, and developments are emerging? The Three Horizons Model offers a useful framework for thinking about change over time and understanding how today's innovations might evolve into tomorrow's systems.

Horizon 1 represents the current dominant system: the way things are done today. It is often efficient but increasingly challenged by problems it can’t solve.

Horizon 2 is the transitional space: where experiments, tensions, and innovations begin to emerge. It includes both incremental improvements and disruptive shifts, some of which may grow into long-term change.

Horizon 3 represents the visionary future: transformative ideas and emerging systems that reflect new values, paradigms, or ways of organizing life and society. While they may seem marginal now, they have the potential to become the mainstream.

This model helps us identify which signals belong to each horizon and how they might interact, enabling us to map out pathways from the present to preferred futures.

Digging Deeper with Causal Layered Analysis (CLA)

Based on these insights, we can go a step further and explore more deeply what desirable future we want to create. One particularly insightful method is Causal Layered Analysis (CLA), which digs into the deeper layers of how we imagine the future:

What metaphors and worldviews shape our visions of the future?

How do our perspectives and assumptions influence what we believe is possible?

What values do we want it to be based on?

And what do we want the future to look like?

By uncovering these underlying narratives, we gain a better understanding not only of where we are headed but also of how our collective imagination shapes urban possibilities. This reflective layer is essential because creating regenerative futures is not only about designing new infrastructures but also about shifting the stories we tell ourselves about cities and their potential. For more tools you should definitely check out Sitra's website!

From Imagination to Strategy: Foresight as a Planning Tool

Overall, foresight methods offer a powerful complement to traditional urban planning tools and urban research. They allow us to look beyond typical 10-year strategies and imagine long-term pathways. They help us ask: What do we want our cities to become? And more importantly: How can we get there?

By integrating future visions into planning and community development, we can better understand the limits of existing systems and explore how transformation can take place. Foresight bridges current realities with alternative futures, inviting us to step outside of business-as-usual and truly imagine what else is possible. In doing so, we not only anticipate what lies ahead, we begin to actively shape it.

Source and continued readings:

Lazurko, Anita & Keys, Patrick. (2022). A call for agile futures practice in service of transformative change: lessons from envisioning positive climate futures emerging from the pandemic. Ecology and Society. 27. 10.5751/ES-13531-270310.

Gall, Tjark & Allam, Zaheer. (2022). Strategic Foresight and Futures Thinking in Urban Development: Reframing Planning Perspectives and Decolonising Urban Futures.

Rogers, Chris & Lombardi, D & Leach, Joanne & Cooper, Rachel. (2012). The urban futures methodology applied to urban regeneration. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Engineering Sustainability. 165. 5-20. 10.1680/ensu.2012.165.1.5.

Sharpe, Bill & Hodgson, Anthony & Leicester, Graham & Lyon, Andrew & Fazey, Ioan. (2016). Three horizons: A pathways practice for transformation. Ecology and Society. 21. 10.5751/ES-08388-210247.

Sitra: https://www.sitra.fi/en/themes/foresight-and-insight/

UNDP. (2028). Foresight Manual Empowered Futures for the 2030 Agenda.

Three Horizon Framework desigend by Lazurko & Keys (2022), based on the original by Sharpe et al. (2016)