Who’s at the Table? Rethinking Participation in Malmö’s Local Development Workshops

This blog reflects on a participatory workshop in Malmö, held as part of the Samskapande Malmö initiative. Through a mix of personal insight and research, it explores how structural imbalances and unequal representation often undermine well-intended participatory processes. The post advocates for deeper collaboration between municipalities and civil society, where power is shared, relationships are reciprocal, and locally grounded solutions can truly emerge.

Marie Urfels

6/11/20254 min read

In urban development, the question of top-down vs. bottom-up approaches is a familiar one. Most planners and policymakers agree: successful local development requires a blend of strategic oversight and grassroots engagement. Yet, despite this consensus, our practice often falls short.

The Workshop: A Missed Opportunity

I recently attended a participatory workshop in Malmö under the theme Samskapande Malmö (Co-Creating Malmö), designed to explore the needs and potential of local development. The city’s Fritidsförvaltningen has been tasked with improving collaboration between municipal departments and local associations to strengthen neighborhood development — an important and ambitious effort.

The initiative was co-organized by Förändringsakademin (The Academy for Change) and Malmö Stad’s Fritidsförvaltning (Recreation Department of Malmö Municipality), who participated both to share their own experiences and to listen to what local actors need in order to strengthen their work. It was part of the broader Samskapande Malmö (Co-Creating Malmö) network, which includes Malmö University, the UNIC university alliance, Förändringsakademin, STPLN, Malmö Ideella, and Fritidsförvaltningen Malmö stad — all working together to promote collaborative, cross-sectoral urban development.

Before attending, I felt energized by what appeared to be an inspiring municipal initiative aiming to include a diverse range of actors in shaping the future of Malmö’s neighborhoods. However, my optimism was quickly tempered. During the introductory session, participants were asked to stand based on their affiliations. Over half the room stood up representing Malmö municipality. In contrast, only a small number identified as NGO representatives, private sector actors, researchers, or unaffiliated residents.

This raised a critical question: Can we truly call it participatory if the majority of voices come from within the municipality itself?

Representation Gaps and Structural Barriers

Malmö is a city where almost half of the population is under 35, with residents from 187 countries and nearly one-third born abroad (Malmö Stad, 2024). Yet, this demographic and cultural diversity was scarcely reflected in the room. While some important civil society groups — such as Rosengård Hus, Hela Malmö, and Idéal Förening — were invited to speak, the broader representation lacked cultural and demographic diversity and sectoral balance.

This reflects a persistent issue in Swedish institutions: structural exclusion and limited accessibility to participatory processes for marginalized communities.

In smaller group discussions, a city official confirmed a finding from my own previous research: when the municipality enters communities with development proposals, they are often met with frustration. Many grassroots organizations have long been active, building trust and initiatives from the ground up, but receive little long-term support or recognition.

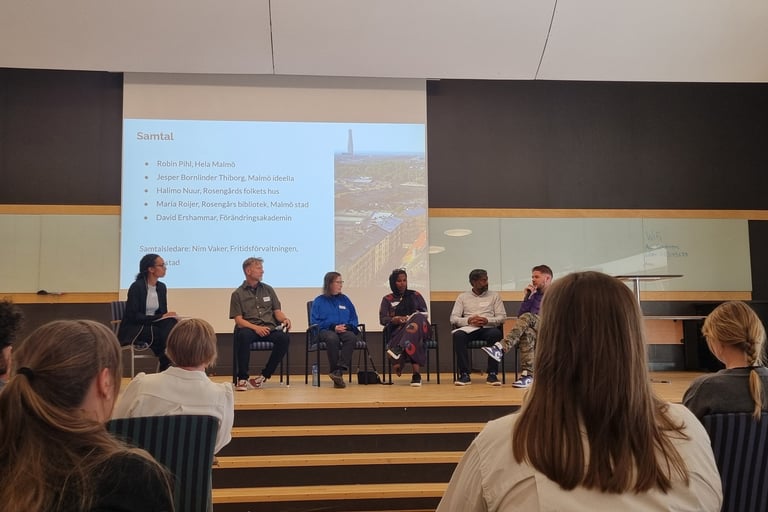

Representatives from Rosengård Hus, Hela Malmö, and Idéal Förening echoed this concern during a panel discussion, emphasizing how municipal systems frequently overlook their contributions. They expressed cautious optimism that the new "gemensam lokal utveckling" process might finally provide a platform where their voices are genuinely heard and valued as equal partners in local development.

This aligns with findings from my 2018 research, in which I interviewed three grassroots organizations. Despite delivering demonstrable success in areas like integration, social cohesion, and environmental improvement, their projects were cut short due to short-term municipal funding cycles. Their experiences illustrate the enduring challenges grassroots actors face in securing long-term institutional support.

The Missing Link: Toward Symbiotic Collaboration

There is no lack of intention — from either side. But the city often recreates initiatives rather than recognizing and reinforcing what already exists. Too often, civil society actors are treated as targets of top-down interventions, not as co-creators of urban change.

To build real collaboration, we need:

Representation that reflects Malmö’s social and cultural diversity

Shared decision-making power across actors

Long-term investment in grassroots initiatives

Institutional structures that value community knowledge as much as technical expertise

Building this kind of symbiotic relationship, where institutions and communities depend on each other to co-create effective solutions, is complex. In this context, symbiosis means moving beyond parallel efforts or top-down control toward a mutually reinforcing partnership where knowledge, responsibilities, and benefits are shared. This is particularly challenging in institutional settings like Sweden, where municipalities are entrusted with significant responsibility for addressing local issues. Their central role in driving urban transformation is legitimate and necessary. However, as in other contexts, the lived impacts of these transformations are felt most directly by residents and civil society actors.

If these voices remain underrepresented or disconnected from institutional efforts, we risk reinforcing the very structural inequalities that participatory processes aim to overcome. Genuine collaboration requires not only intention but also active inclusion, mutual respect, and shared ownership of both challenges and solutions

Call to Action: From Talk to Transformation

After the workshop, I was left hopeful, but cautious. The willingness to change is real, but old patterns persist. We risk reproducing the very structures that have hindered equitable development for years.

We need both a cultural and structural shift:

One that embraces discomfort and shared learning

One that recognizes residents, especially in underserved neighborhoods, as agents, not passive recipients

One that fosters ongoing dialogue, transparency, and accountability

We need to move beyond the binary of top-down vs. bottom-up. Symbiotic relationships between institutions, civil society, and residents, where power, knowledge, and resources are co-produced, is highly needed to transform these structural barriers. Only then can urban development genuinely reflect the people it aims to serve.

Panel discussion with represnetative of Förändringsakademin, Rosengård Hus, Hela Malmö, and Idéal Förening.